The Biden administration’s announcement that up to $20,000 in student loan debt will be canceled for borrowers will bring welcome relief to millions, as long as courts allow. But that relief won’t do anything to slow the rapidly rising cost of going to college.

In the 1963-1964 academic year, the average annual published cost of in-state tuition and fees was $243 at public four-year institutions, and $1,011 at private four-year institutions, according to National Center for Education Statistics data. That excludes room and board.

If the published cost of college remained in line with inflation, annual tuition and fees would have been $2,076 at four-year public universities and $8,624 at private institutions for the 2020-2021 academic year, according to the National Center for Education Statistics’ data in constant dollars, or income adjusted for inflation.

But in the 2020-2021 academic year, the average price tag for in-state tuition and fees at a four-year public institution was $9,375, and at private four-year institutions, it was a whopping $32,825. With student housing, that cost skyrockets — some schools are charging those who can afford it over $70,000 per year.

Why is college so expensive?

“There’s no one single answer,” says Beth Akers, author of “Making College Pay” and a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. “You can ask lots of different people and they have lots of different reasons.”

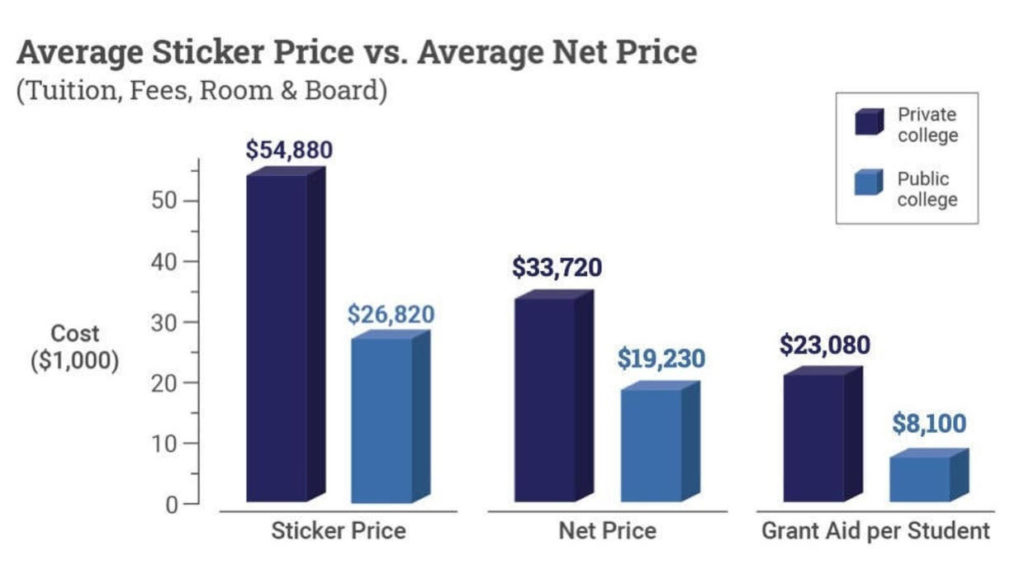

However, the sticker price an institution lists on its website and the net price can be pretty far apart, said Phillip Levine, an economist at Wellesley College. The net price is what students pay after needs-based aid and merit scholarships. The net price has increased at a faster rate at public institutions, where state funding hasn’t kept pace with the increase in price.

The government doesn’t track the net price students pay at public vs. private institutions. But according to the College Board, students on average receive more financial aid at private institutions. And the net price families paid at private colleges for tuition, room and board was about $33,720 at private institutions, compared with $19,230 at public colleges for the 2021-2022 academic year.

In the last two decades, the published price of tuition and fees at private four-year institutions has increased much more rapidly than the net tuition. Over the last 20 years, their sticker prices have gone up 54% in inflation-adjusted dollars, even though net tuition prices — what students are paying after factoring in grants and scholarships — have gone up just 7%, according to College Board and National Center for Education Statistics data analyzed by the Manhattan Institute.

For many public institutions that have been seeing decreases in state funding, the financial picture is worse. The published price for tuition and fees has increased 102% at public four-year institutions, adjusted for inflation, with net tuition and fees at public four-year schools running 115% higher in the last 20 years.

“A lot of times we overestimate the rising cost of college,” Levine said. “Because mostly what we do is focus on the sticker price.

But the vast majority of students don’t pay the sticker price at public or private schools, he said.

Public institutions have “shifted away from funding through taxpayer support and toward collecting revenue through individual tuition charges,” said Akers.

Students from upper-middle class and affluent families who often comprise the governing and media classes are the ones paying full price, Levine noted.

“The discrepancy is that’s the price that high-income families have to pay,” Levine said.

Administrative costs and facilities

The number of administrative staff added at higher education institutions has outpaced the hiring of teaching faculty in recent decades.

The number of administrators at higher education institutions grew twice as fast in the 25 years ending in 2012 as the number of students did, the New England Center for Investigative Reporting found by analyzing federal data.

And from 2010 to 2018, spending on student services increased 29% and spending on administrative functions increased 19%, while spending on instruction only grew 17%, according to a 2021 report from the American Council on Trustees and Alumni.

Colleges and universities have become more comprehensive in the services that they offer, and in general, students are reaping the benefits, said Janet Napolitano, the former Arizona governor and former secretary of the Department of Homeland Security who was president of the University of California system for seven years.

“I never had students come to me and say, we need fewer Title IX officers, or we need to reduce mental health services or we need to reduce the number of people who help in the financial aid office,” said Napolitano, who is now the director of the Center for Security in Politics at the University of California, Berkeley.

“The point being is that over time, as universities have absorbed the cost of providing not just the academic teaching and research aspect of a college education but all the kind of adjunct or associated services that go along with it, that, too, has I think added to the cost.”

But administrative spending doesn’t account for most of the increase in the sticker price of college, Akers said.

Then, there are the headlines about luxury amenities for students, like lazy rivers at Texas Tech University, or climbing walls at the University of Maryland. But those additions are also facile targets, and still don’t come close to explaining the increase in the sticker price for college, Akers said.

Market forces

Higher education is competitive — Harvard and Princeton will always be competing for the same very select pool of the nation’s most promising students.

“It’s also the case that in some ways higher education doesn’t look like a normal market,” Levine said.

In a normal market, everyone pays the same price. “Everyone doesn’t pay the same price in higher education,” Levine said. At many schools, those who can afford less pay less, and at a handful of the nation’s most elite schools, including Harvard, Yale and Stanford, students who are accepted and whose family income is under around $60,000 get a free ride.

That lack of price transparency in what the net price will be for a prospective student is aso something that distorts the market, Levine noted, since most college applicants don’t know what they’ll actually pay until after they’re accepted, commit to a university and apply for aid.

Levine created a tool, MyinTuition, through which students can estimate their net tuition cost based on factors like how much their family has in savings and investments, their GPA and their SAT scores. He built the tool when he was trying to figure out how much he would pay for his own kids’ college education.

But his website doesn’t include the majority of higher education institutions, and the calculator is just an estimate, and isn’t binding.

Student loans

Then there are student loans.

“People claim all the time the fact that we’ve allowed people to borrow so much is driving up the price, and I think there’s some truth in that,” Akers said.

“It’s not really a basic economic argument that the availability of loans has driven up the price, but I think it’s more of a behavioral thing.”

Millions of Americans will continue to attend college and take on mountains of debt to do so because the financial — and even social — benefits of attending college still generally outweigh the financial cost, Akers and Levine each noted.

“The returns to graduating from college are significant,” Levine said. “And simple calculations basically will indicate that for the typical student, attending college definitely pays off relative to its cost.”

But “that doesn’t mean it pays off for everybody,” Levine added.

Men with bachelor’s degrees earn about $900,000 more in median lifetime earnings than their high school graduate counterparts, according to Social Security Administration data. Women with bachelor’s degrees earn $630,000 more during their lifetimes than women with only a high school diploma.

And a 2021 study from Georgetown University found high school graduates make a median of $1.6 million during their lifetimes, compared to $2.8 million for those with bachelor’s degrees.

So, over the span of a lifetime, spending say $100,000 for a college education with those returns is a relative “bargain,” Akers said.

Millions will continue to pay more and more for college, so long as the benefit generally outweighs the cost. But at some point, “the market forces will continue to drive up the price until it’s no longer worth it,” Akers said.

Napolitano is skeptical of the Republican argument that universities will use the Biden administration student loan forgiveness as an opportunity to significantly ratchet up prices.

“I think any college president who relies on the assumption that loans in the future will be canceled is living in a fairy land,” she said.

Are there any solutions?

Akers said the solution to addressing the ever-increasing cost of college is the opposite of the student loan cancellation the Biden administration is undertaking.

That said, “I don’t want to eliminate subsidies,” said Akers. “I don’t want to eliminate the student loan program.”

But graduates who can afford to pay back loans should be required to do so, she said.

One avenue to reducing costs would be cutting the time it takes to obtain a college degree. If students are able to receive college credit for coursework while they’re still in high school or even middle school, that would shorten the time they’re paying for four-year colleges. Napolitano, for instance, thinks state governments should further incentivize students to attend community college, to attend far less expensive community colleges, both while they’re still in high school and after, so they can transfer those credits to a four-year institution.

There also should be more pathways to securing good, well-paying jobs, Akers said, adding she thinks there’s “going to be kind of a natural correction,” with more employers dropping requirements for college degrees. Some companies have already begun to do that in today’s tight labor market. Apprenticeship programs and trades should be celebrated, she argued, saying that political and social leaders need to celebrate those pathways, too.

This article was published on CBS News.