Make it easier to estimate real costs, and more students may take a chance on elite colleges

by MIKHAIL ZINSHTEYN

Yuna Ishikawa was in her senior year of high school in 2014 when she made the drive with her mother from Oberlin, Ohio, to visit Wellesley College in Massachusetts. She loved the place, but not its price tag: $60,000, well beyond her family’s means.

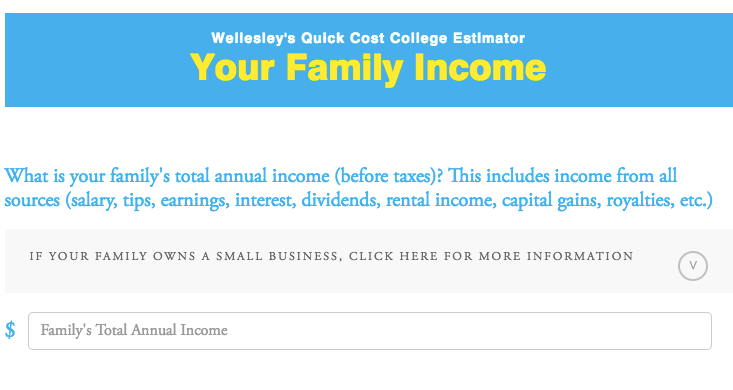

Then the admissions counselor showed her something new – MyinTuition, a six-question survey that takes only a few minutes to fill out and predicts with surprising accuracy just how much financial aid a student can anticipate from the college.

It’s the creation of Phillip Levine, a Wellesley economics professor who was frustrated by trying to forecast the cost of sending his own children to a university.

“I found it next to impossible to figure out the answer to that question,” Levine said. “I have a Ph.D. in economics; I’m pretty good at this sort of thing. If it’s difficult for me, that’s a problem.”

For students who assume that an expensive college is out of the question, no matter how good their grades are, Levine’s tool could be a breakthrough. And it could be particularly effective for recruiting low-income students who don’t know that the actual cost and the “sticker price” can differ dramatically.

During college fairs or campus visits, a college representative using MyInTuition can hand a student a smartphone or a tablet, allowing him or her to input familiar household income information and receive a likely financial-aid estimate on the spot.

“It’s often difficult for families in general, but perhaps especially low-income families, to move past the shock of the sticker price of a place,” said Elizabeth Creighton, deputy director of admission at Williams College, which also uses Levine’s tool. “That’s one of the reasons we make sure prospective students know about MyinTuition and how simple it is to use.”

Back home in Ohio, Yuna and her mother tried the tool.

“We were surprised at how easy it was,” she said; the whole process took a few minutes. The calculator predicted that, given her family’s finances, the school would award her enough financial aid to cover the cost of tuition and fees – about $49,000. “We couldn’t believe it. We laughed it off,” she said.

It turns out the tool was off: When Yuna was accepted in mid-December that year, her financial aid letter stated she’d receive $1,000 more than the calculator predicted. She’s now a sophomore at Wellesley, and employed by the admissions office as a campus tour guide. Her tuition is still covered.

Despite their smarts, low-income students who have the grades for the nation’s top schools often don’t know that expensive colleges sit on piles of financial aid that could make them affordable. One famous study by researchers Caroline Hoxby and Christopher Avery found that high-performing, low-income high school students submit college applications to far less selective schools than their equally talented but wealthier peers, denying themselves the opportunity to earn degrees among the nation’s brightest, and enrolling instead in schools that tend to have higher dropout rates and smaller financial aid packages.

Like other net-price calculators – the federal government makes one available, and other colleges have created their own – MyinTuition asks students to provide basic information about their household’s financial situation, then compares those numbers to the financial aid the college is likely to provide. Federal rules allow colleges to use the federal government’s version or create their own, as long as they provide the same type of information, such as the types of loans and grants available and the likely cost of books, food and housing.

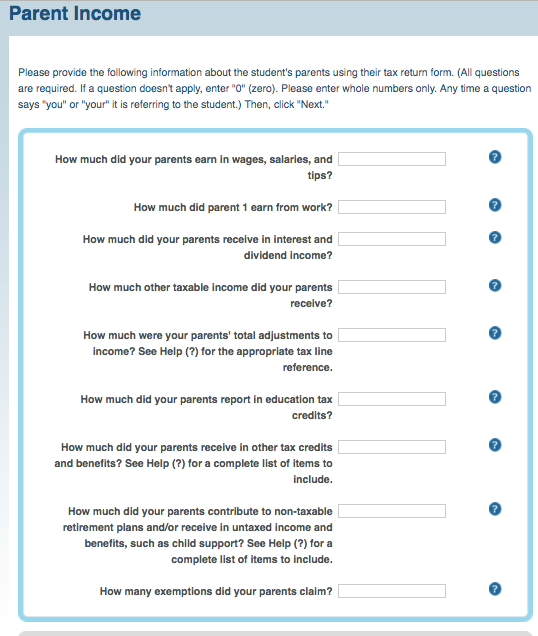

The questions MyinTuition asks, said Levine, are ones “that people generally have the ability to answer without looking up tax records or calling an accountant or figuring out anything else.” Whereas Levine’s tool asks six questions, other net-price calculators may require families to spend at least 20 minutes answering many detailed questions about home finances.

Especially for low-income students, many questions on these calculators (about investment income or pensions, for example) don’t represent the financial realities of their homes. Andrew G. Biggs, a scholar on retirements at the American Enterprise Institute, crunched data using the Survey of Consumer Finances for The Hechinger Report. He found, for example, that about two-thirds of households with annual incomes less than $50,000 and headed by people in the 40- to 50-year-old range have no retirement savings. By contrast, nearly three-quarters of households with incomes of $200,000 or more and headed by adults aged 40 to 50 do have retirement savings.

The longer net-price calculator designed by the College Board, meanwhile, asks many more questions.

Levine cited an analysis Wellesley commissioned two years ago of how many visitors to the website completed both MyinTuition and the school’s then-standard net-price calculator. Around 80 percent fully answered MyinTuition’s questions, while 30 percent went all the way through the other calculator.

Right now three colleges use the tool – the University of Virginia, Williams and Wellesley. Levine said 12* other selective colleges will begin using it in the spring (he wouldn’t reveal their names).

QuestBridge, a program that matches talented low-income applicants with 38 elite colleges, is encouraging its member schools to use Levine’s tool. Last year Wellesley gave $100,000 to fund Levine’s efforts.

MyinTuition is also prominently featured on Wellesley’s website, at the top of the financial aid section. Often on the websites of even top public universities known for wanting to enroll low-income students, the net-price calculators are harder to find. (The University of California, Los Angeles, for example, takes an applicant through a half-dozen webpages and many lines of text before arriving at a link to the calculator.)

“They’re buried on websites,” said Lindsay Page, a scholar who researches the behaviors of college-bound students. One of her graduate students at the University of Pittsburgh has preliminary data showing that the term itself – net-price calculators – confuses some talented low-income students. Page’s research also shows that some leading colleges’ net-price calculators are inaccurate because they use half-decade old tuition information as the basis for their calculations.

But supplying students with timely information isn’t enough, Page said, even when it’s presented in a consumer-friendly way. She pointed to a study conducted by researchers at the College Board and Georgia State University that tracked where students sent their SAT scores after viewing the Department of Education’s data on the typical earnings among graduates of certain colleges.

“What they find is essentially preferences are only changed by students from well-resourced backgrounds in well-resourced high schools,” she said. “The optimistic hope is that the availability of this information will help everybody make better decisions,” but in practice only the wealthier students took advantage of the data.

She’s not short on hope for strategies that do steer more high-scoring, low-income students toward wealthier colleges, though. Customization is key, she said.

Another study by Hoxby and Sarah Turner sent information to low-income students with high SAT scores identifying selective colleges that would welcome their test results, plus information on how to submit their college applications for free. The effort cost about $6 per student and resulted in more low-income students applying to highly selective colleges.

*Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated the number of colleges expected to begin using the tool in the spring; it is 12, which would bring the total to 15 colleges.

This story was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Read more about higher education.